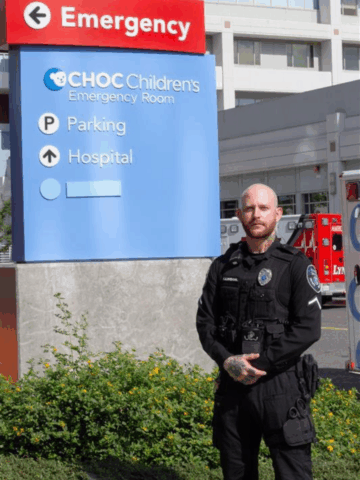

By Dr. Peter T. Yu, pediatric general and thoracic surgeon at CHOC

5:00 a.m.: Alarm rings. I hit snooze once, for an additional 9 minutes of peace. Then it is time to get up and at ’em. In the dark, I attempt to avoid injuring myself on the various toys that are strewn about the house–one of the hazards that comes with raising young children. I start the coffee maker, brush my teeth, shave, get dressed and kiss my slumbering family good-bye. Then it is off to swim practice.

7 a.m.: Swim practice is over. Fatigued but happy, I shower and joke with the teammates on my masters swim team. I am grateful for my health and momentarily enjoy the small personal accomplishment of having completed my workout for the day.

7:30 a.m.: After navigating moderate traffic and enjoying NPR, I arrive at CHOC. I meet with the very kind family of my first patient, a 5-year-old boy who is having inguinal hernia/hydrocele surgery today. In children, an inguinal hernia is a small, congenital opening in the groin that allows communication between the abdomen and the scrotum in boys and the labia in girls. Thus, things like fluid, fat, omentum or intestines can pass through this opening, creating a bulge and sometimes causing pain. A hydrocele is related to an inguinal hernia and is due to fluid that has passed from the abdomen, through the opening, and into the scrotum. Inguinal hernias occur in about 1-5 percent of all children. Hernia and hydrocele surgery are routine operations for all pediatric general and thoracic surgeons and, as expected, the operation goes smoothly.

9:00 a.m.: For my second operation of the day, Dr. Mustafa Kabeer, a fellow pediatric general and thoracic surgeon, and I perform a minimally invasive Nuss procedure on a teen athlete. This patient, who hopes to earn a college scholarship, has pectus excavatum or sunken chest, the most common congenital chest wall abnormality in children. For many, this is far more than a cosmetic problem. Using small incisions that will ultimately be well-hidden in this patient’s armpits, we are able to insert a metal bar between his heart and his chest wall that helps to pop the sternum out into normal position. This bar will stay in place for three years, before it is removed in an outpatient procedure. Our operation today took only 2 small incisions and 45 minutes of operating time. We prefer the minimally invasive Nuss procedure to the older, more invasive Ravitch procedure since it achieves a wonderful outcome with less pain, minimal blood loss and only tiny, hidden scars.

10:00 a.m.: As the anesthesiologist and the operating room staff prepare for my final case of the day, I walk over to the surgical neonatal intensive care unit and medical/surgical unit to make rounds and touch base with my team of excellent, experienced surgical nurse practitioners (NPs). Not a day goes by that I am not thankful for their contributions to the outstanding care of our surgical patients at CHOC. Currently, on the surgical floor, I have patients who have recently had appendectomies, a cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder), lysis of adhesions (cutting of intra-abdominal scar tissue) to treat a small bowel obstruction, port placement for chemotherapy, and a Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. In the NICU I have one baby with congenital diaphragmatic hernia whom I recently placed on ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), state-of-the-art technology that supports the heart and lungs by taking over the heart’s pumping function and the lung’s oxygen exchange. A second patient of mine in the NICU is a baby who recently had esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula surgery to repair a congenital defect where the trachea, or windpipe, abnormally communicates with the esophagus, or food tube. Fortunately, all patients are doing well, I am able to address the questions of each of my patients and their parents, and the NPs and I come to a consensus on the plan of care for the day for each one.

10:30 a.m.: Once rounds are done, I head back to the operating room for my final case of the day, a thoracoscopic lung lobectomy. This is one of my most favorite operations and is my area of expertise. This 3-month-old patient was diagnosed prenatally when an ultrasound showed a congenital lung lesion, also known as a CPAM (congenital pulmonary airway malformation, formerly known as CCAM). This diagnosis is becoming more and more prevalent, occurring in about 1 in every 5,000 babies. Fortunately, more than 90 percent will be symptom-free during pregnancy and after birth, allowing pediatric general and thoracic surgeon such as myself to hold off on surgery until the infant is a few months old and better able to tolerate the stress of an operation. Even though infants with CPAMs may be asymptomatic, it is still recommended that these lesions be removed because they can often become infected and, in rare instances, may become a cancer later in life. The benefit of operating sometime during the first several months of life is that the CPAM has yet to become infected, making surgery easier and allowing for a minimally invasive removal. Thanks to the patient’s young age, the remaining portion of her healthy lung will grow in size and compensate for the removed lobe.

Thoracoscopic lung lobectomy is extremely technically challenging because the surgeon navigates major blood vessels such as the pulmonary artery and pulmonary vein, and operating time can vary from two to six hours depending on a patient’s particular anatomy. Fortunately, this little baby’s anatomy is favorable and I am able to complete the minimally invasive operation in about 2 hours with minimal blood loss and an excellent outcome. After surgery, I have the privilege of giving her parents good news, which is always the best part of my work day. I anticipate that she will have a two-day hospital stay with minimal pain and no complications, and her tiny scars will ultimately be unnoticeable by others (except for mom! Pediatric surgeons know that moms see everything).

1:00 p.m.: I have a quick lunch with my NPs and Dr. David Gibbs, another pediatric general and thoracic surgeon at CHOC who is also the medical director of trauma. He has established the excellent trauma program we have here, the only trauma center in Orange County that is exclusively dedicated to children. We take a moment to enjoy each other’s company, get trusted input on current clinical situations, and catch our breaths from this very typical, fast-paced workday.

2:00 p.m.: I participate in a fetal counseling session. Given my special training in fetal surgery, I work closely with community perinatologists (also known as high-risk obstetricians or MFMs–maternal fetal medicine physicians) to counsel expectant mothers and fathers on what to expect when their baby has been diagnosed in utero with a condition that will require surgery.

Today, I meet with parents whose daughter has been prenatally diagnosed with congenital diaphragmatic hernia, or CDH. Simply put, CDH is a hole in the diaphragm, which is the muscle that divides the abdomen from the chest. The diaphragm helps us breathe, and a hole here allows things that are normally in the abdomen, such as the liver or intestines, to pass into the chest. Besides potentially compromising the intestine itself, this can also lead to small lungs (pulmonary hypoplasia) which may not be able to adequately oxygenate the body. Another severe consequence of CDH is pulmonary hypertension, which is abnormally high pressure in the blood vessels of the lungs. This is a problem because a newborn’s heart must work extra hard to pump blood into this abnormal high-pressure system, which can lead to heart failure and death if not appropriately treated.

I go over the diagnosis with mom and dad, and explain to them that, after birth, their baby will require a breathing tube and ventilator to support her small lungs. Special inhaled and intravenous medications will be used to decrease the high blood pressure in the blood vessels in the lungs and to help support her beating heart. If these measures are not enough, we will need to use ECMO. If ECMO is needed, I will perform a surgery to make an incision on her neck to access her carotid artery and jugular vein so that ECMO catheters can be placed.

Ultimately, once their daughter’s heart and lung condition has stabilized—which may take days to weeks after birth—I will repair the congenital diaphragmatic hernia. To do this, I will make an incision on the abdomen, move the intestines and liver from the chest back into the abdomen, and stitch the hole closed.

I am careful to be upfront and honest about the situation: CDH is a serious and frequently life-threatening condition and the national average for survival is approximately 65 percent. Their daughter will likely require a two to three month stay in our NICU and may need to go home with supplemental oxygen and special medications for a period of time. However, I’m able to reassure them as well. Nearly 90 percent of newborns that have this surgery at CHOC survive. At CHOC, we are fully equipped and have the expertise to handle any possible outcome, thanks in part to our surgical NICU, the only one of its kind of the west coast.

Mom and dad are tearful at the gravity of their daughter’s situation but they also express how grateful they are for the opportunity to learn more about CDH, have their questions answered, and leave feeling better prepared for the next steps. They know they can contact us at any time, day or night, and we will be there to address any problem and provide support. They also feel relieved that they will be surrounded by familiar, trusted faces when their daughter is born.

3:00 p.m.: I head back to my office with some precious time to complete some homework—yes, I said homework—and work on research projects. Believe it or not, I have gone back to school to get my Master of Public Health degree from Johns Hopkins University. This is feasible because I am able to complete the majority of my coursework online. I wanted to get this additional degree to gain knowledge and experience in outcomes research, a relatively new branch of public health research that seeks to understand the end results of particular health care practices and interventions. While pursuing this degree, I am simultaneously working on outcomes research projects with my research partner, Dr. Yigit Guner, another pediatric general and thoracic surgeon at CHOC. Together we are utilizing large national databases to create risk calculators that can help better predict CDH outcomes, as well as predict outcomes in other neonatal diseases such as VACTERL (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, trachea-esophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities).

6:00 p.m.: I head home for the day. En route, I call my mother who lives out-of-state to check in. My father recently passed away after a long struggle with illness and I just want to make sure she’s doing alright. She assures me that she is, and stubbornly resists my suggestions to have her move to Orange County. She is happy and comfortable in her home, which makes me happy as well, but I am concerned that I will be unable to adequately help her in the years to come should her health someday fail.

6:30 p.m.: I’m happy to be home with my family. It’s dinner time and I’m famished. I relish the chance to catch up on the day’s events with my wife and kids. I play with the kids for a bit and then it is time to help my oldest with homework. After that, my wife and I get all the kids ready for bed and tuck them in.

9:00 p.m.: My wife and I finally have a precious moment to ourselves. We watch a favorite TV show together and I barely make it to the end before falling asleep. It feels so good to lie in bed, with the cool night breeze filtering in through my bedroom window. I dream of my family, work and old friends. Tomorrow, I have clinic and then I will spend the remainder of the day and night in the hospital, as I am on call for any pediatric general, thoracic and trauma emergencies that come to CHOC. I feel so blessed to have the family that I have, and to be able to do the meaningful work that I do.